Why are there no obese animals

Can wild animals become overweight?

Can wild animals become overweight?

Under our care dogs and horses can get fat just like human beings. But can animals in nature get too fat?

When we humans get easy access to butter and donuts many of us end up with double chins and spare tyres faster than you can say candy. But what about wild animals asks one of our readers?

What are the chances, for instance, of seeing a corpulent moose trotting out of the forest? Or a ferret with a beer gut??

Not particularly great, if we can trust Petter Bckman, a zoologist at the Museum of Natural History in Oslo.

Nearly impossible

Its almost impossible for wild animals to get too fat, says Bckman.

If you are carrying lots of dead weight around you are going to have difficulties moving. Youll get less food and become trim again. Just consider a fat cheetah. It wouldnt be able to outrun a gazelle."

Its easy enough to understand that predators have to stay fit to get their claws into prey. But what about large herbivores without many dangerous enemies? Elephants in an a vast sea of grass, for instance. Cant they get fat?

Non-nutritious food

Elephants live on a bare minimum. They are really slim! They have big stomachs because they eat loads of food that is almost indigestible, says Bckman.

This is a challenge for all animals that live on food that is plentiful, like grass or leaves. Such fare lacks nutrition. You have to stuff yourself with huge amounts to get sufficient energy.

Its a little like eating a packet of instant soup mixed into a whole bathtub of water. It takes a long time to get enough of it and the animal also expends lots of energy moving around to consume it.This means that the energy budget just barely stays out of the red. This is why in cold periods we find dead roe deer with their stomachs full of food, explains Bckman.

Some do get stout

According to the zoologist, the only opportunities animals have to get fat are when they happen upon large amounts of nutritious food. This can almost only happen with rodents like mice and rats.

In addition any mountain of food can only be available in an unexpected circumstance, for a short while. Otherwise a whole bunch of different animals would be there competing for the food. Even in such situations you rarely see obese little animals.

Because what do rodents, who usually live on the verge of starvation, do when they suddenly get a big surplus? They start to produce offspring straight away!Such small animals need only a month to get a whole new generation up and running. So fairly soon you get a large number of trim mice instead of a handful of fatties, says Bckman.

But wait a second! It cant be impossible to grow podgy in nature. Penguins are said to be so full of fat that they can be used to fuel a fire. And arent harbour seals just big blubbery sausages of the sea?

Relative fat concept

Some animals are fat by human standards, says Bckman.

"Seals, whales and sea elephants have thick layers of fat. But these are species that live in frigid temperatures and frigid waters. If they slim down they will freeze to death. So could you call them overweight?" asks Bckman

Other animals also gain weight when there is a surplus of food around.

Bears eat like crazy in the summer and are fairly chubby in the autumn. But then comes the hard times. The surplus fat is burned surviving the winter.

"Thats how it should work with us humans too," says Bckman.

Our brother the bear

In Norwegian nature, bears are the animals closest to us, according to the zoologist. A bear has to eat readily digestible food like we do. When it comes across lots of food it stores the surplus as fat.

We humans are actually a tropical animal species adapted to an environment with little food. We are programmed to put on weight so that we can make it through famine. But for most of us now there is no famine, says Bckman.

So we stay fat, with all the health problems that entails. Bears, however, avert metabolic syndromes and cardiovascular diseases.

Bears are just fat for a few months. If I had been obese as a 20-year-old, then skinny as can be after a famine when I was 21, and then a bit fat again when I was 23 I would just be a little chubby on the average, says Bckman.

Our problems are also linked to our longevity.

Evolution against overweight

If we had lived out in nature like other mammals we would reach an age of 25 to 30. Studies of Cro-Magnon humans and Neanderthals show that few passed the age of 35.

"In those two or three decades you hardly have time to develop cardiovascular disorders.But the human environment has changed so much that the bodys storage functions are causing us problems. But time will cause adjustments, says Bckman.

Human evolution has never run so rapidly as now. Those who can handle access to a lot of food better and stay healthy and fit have more surviving children. So, future generations should be better adapted to the situation.

We can already observe this phenomenon in animal species that live on unhealthy food from human garbage tips. Many of them suffer from metabolic disorders. But others tackle the diet better and these are the ones who have the most offspring. Thats how species adapt as time passes.

In 50 generations obesity will be rare among humans too, says the researcher.

But that is if our present diet continues for the next 1,250 years. Thats probably not very likely.

-----------------------------------

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling

Related content

Can wild animals become overweight?

In 2019, firefighters in the German town of Bensheim rescued a chubby rat that had become stuck trying to squeeze itself through a small gap in a manhole cover. The rotund rodent was sent on its way with a valuable life lesson: that overeating isnt necessarily a good idea.

Overweight animals are slow and vulnerable to predation, so dont last long. The animals we think of as fat seals, walruses and polar bears arent overweight at all. Their blubber is an adaptation that offers buoyancy, insulation and energy storage, so sometimes its all about survival of the fattest.

Read more:

undefined

Obesity On the Rise in Animals

The problem of obesity isn't confined to just humans. A new study finds increased rates of obesity in mammals ranging from feral rats and mice to domestic pets and laboratory primates.

Americans have grown increasingly heavier, with the average body mass index (or BMI, a measure of height and weight that estimates fatness) increasing from about 25 in the early 1960s to around 28 in 2002, according to the Centers for Disease Control. The CDC considers adults with BMIs between 25 and 29.9 to be overweight.

Increasingly caloric diets and lack of exercise are usually cited as major causes of human obesity. These factors undoubtedly play a role in Americans' expanding waistlines, said lead study researcher David Allison of the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

However, Allison said, the new obese animal findings point to additional, yet-unidentified causes for the uptick in obesity.

"We can't explain the changes in [the animals'] body weight by the fact that they eat out at restaurants more often or the fact that they get less physical education in the schools," Allison told LiveScience. "There can be other factors beyond what we obviously reach for."

Plump primates

Allison first stumbled across evidence of overweight animals while looking at data on marmosets from the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center. The average weight of the monkeys had gone up over the decades, he noticed, and there seemed to be no plausible explanation. Allison queried primate center researcher Joseph Kemnitz as to what the cause might be: Were the marmosets from a different supplier? Had they been bred to be larger? The answers were "no" and "no."

Get the worlds most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the monkeys' diets had been changed over the years, a switch that was well-documented by the lab. So Allison tried running the numbers again, this time controlling for the diet change.

"It only made the results stronger," he said. With the diet change, the animals should have lost weight, if anything.

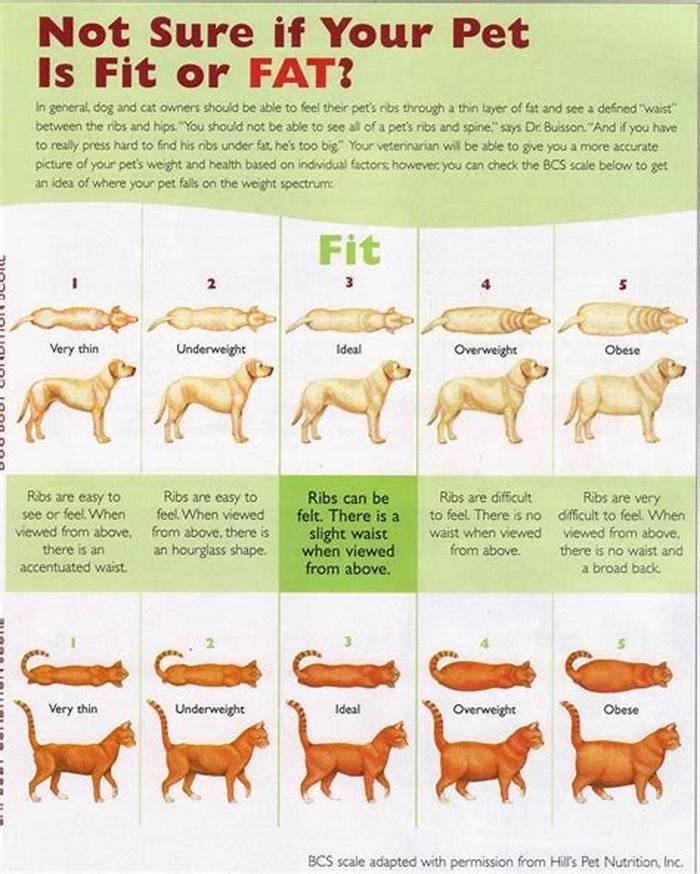

Intrigued, Allison and his colleagues decided to investigate more thoroughly. They gathered data from over 20,000 individual animals living in 12 distinct populations. There were eight species in total: laboratory macaques, chimpanzees, vervet monkeys, marmosets and mice, as well as domestic dogs, domestic cats, and domestic and feral rats from both rural and urban areas. [Read: Is Fido Fat? Human Diet Tricks Could Help]

All of the populations had weight records stretching into the second half of the 20th century. Only control groups of lab animals were included to rule out any effects of treatments or experiments on obesity. Weights were measured at midlife and were available at several time points as late as 2006.

Body weight increases

The researchers split the 12 populations into male and female sets for a total of 24 groups. They then analyzed each population to find out the percent change in body size over time.

"In 24 out of 24 cases, the slope of that percent body weight change was increasing," Allison said. "It strongly suggests that there is something going on."

In a second analysis, the researchers designated the heaviest 15 percent in the earliest weight data for each animal as "obese" (while human obesity starts at a BMI of 30, there is no universal definition of obesity for animals). They then used those weight points to see how many animals in each population fit into the obese category as time passed. This time, the percentage of obese animals increased in 23 out of 24 cases.

The size of the change varied by species, but was often quite significant, Allison said. For example, the researchers report today (Nov. 23) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B that macaque body weight increased 7.7 percent per decade for males and 7.9 percent per decade for females. Male mice ballooned by 10.5 percent per decade and female mice by 11.8 percent per decade.

Meanwhile, female cats got larger by 13.6 percent per decade, and male cats grew by 5.7 percent. Dogs experienced a 2 to 3 percent increase in body weight per decade. Even feral rats got larger: Male rats from Baltimore increased in size by 5.7 percent per decade and female rats by 7.22 percent. Rural rats showed similar, though slightly smaller, increases.

A complex problem

"It just highlights how little we understand about what's happening in terms of why we see this rise in body weight in our population," Jennifer Kuk, an obesity researcher at York University in Toronto who was not involved in the research, told LiveScience. "Perhaps this problem isn't as simple as just energy intake and energy expenditure, which has been the prevailing message over the last 10 years."

While it's not surprising that pets should be getting fatter along with their owners, or even that rats might be getting bigger by eating calorie-rich human garbage, Kuk said, the increase in body weight in controlled lab animals is unexpected.

There are several theories as to why animals and humans might be getting fatter even without the help of fast food and desk-jockey jobs, Allison said. Pathogens could be to blame: A virus called adenovirus 36 has been linked to obesity in both humans and animals. Hormone-disrupting compounds, or endocrine disruptors, have been shown to trigger obesity in mice exposed to the compounds in utero.

The change could be something as simple as our increasingly artificial environments, Allison said. Light pollution and sleep disruption have been linked to obesity. It's even possible that air conditioning and central heat are to blame.

"In the winter, you're not expending as much energy, because the room is kept warmer," Allison said. "In the summer, it doesn't get so hot, and we know that heat drives food intake down."

Allison emphasizes that these factors are only speculation at this point. Multiple researchers are investigating the factors, which may be the key to understanding the human obesity epidemic, Kuk said.

"If the number of calories going in is the same over time, and there's a net gain, then obviously the way those calories are managed is different or something has changed," Kuk said. "Why that management of calories is changing is going to be important if we're going to reverse the trends."