What is treatment prevention of obesity

Treatment for Overweight & Obesity

Most often, health care professionals treat overweightand obesityby helping you adopt lifestyle changes that may help you lose excess weight safely and keep it off over the long term. In some cases, other treatments such as weight-loss medicinesor weight-loss surgerycan be helpful.

How much weight should I lose?

If you need to lose weight, work with a health care professional to set a weight-loss goal and time frame that will work best for you. For example, losing 5% of your body weight over a period of 6 months may be a good initial goal.34 If you weigh 200 pounds, this would mean losing 10 pounds.

Losing excess weight may help lower your chances of developing health problemsrelated to overweight and obesity. If you already have weight-related health problems, such as high blood pressureor diabetes, losing weight may help improve your health.

How do health care professionals treat overweight and obesity?

Lifestyle changes

Health care professionals often treat overweight and obesity by recommending lifestyle changes, such as adopting a healthy eating plan and increasing your physical activity, to help you lose weight safely. These lifestyle changescan help you reduce the caloriesyou take in from food and beverages and increase the calories you use up by being active.

Tailored weight-loss program

In some cases, your health care professional may refer you to a health care specialist or a health care team trained in weight management. These specialists will design a plan just for you and help you carry out your plan.

Safe and successful weight-loss programstypically include32

- 14 or more weight-loss counseling sessions conducted over 6 months

- an eating plan based on the calories and nutrients your body needs

- at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity, such as brisk walking or cycling

- daily monitoring of food intake and physical activity, and weekly monitoring of weight

- regular feedback and support from specialists

When combined with healthy eating, regular physical activity may help you lose weight and stay at a healthy weight.

When combined with healthy eating, regular physical activity may help you lose weight and stay at a healthy weight.You may work with the specialists in individual or group sessions. The sessions might be held in person or online using smartphones, computers, or other devices. The specialists may contact you regularly by telephone or email to help support your plan. Smartphone apps and other tools may help you track how well you are sticking with your plan.

Weight-loss medicines

Weight loss can be difficult to achieve and maintain. When lifestyle changes are not enough, your health care professional may prescribe medicines to treat overweight and obesity.Some medicines can also be used to help you maintain weight loss. You should try to stick with your healthy eating plan and stay physically active while taking weight-loss medicines.

Weight-loss surgery

Weight-loss surgery, also called metabolic and bariatric surgery, includes several types of operations that help you lose weight by making changes to your digestive system. Your doctor may recommend weight-loss surgery if you have a body mass index(BMI) of 35 or higher. Some doctors and professional groups recommend weight-loss surgery for people with a lower BMI if they have a serious health problem related to obesity, such as type 2 diabetesor sleep apnea.35,36

Weight-loss devices

Your health care professional may consider weight-loss devicesif you havent been able to lose weight or keep off the weight you lost using other treatments. Because weight-loss devices have only recently been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, researchers dont know the long-term risks and benefits.

References

[32] Wadden TA, Tronieri JS, Butryn ML. Lifestyle modification approaches for the treatment of obesity in adults. American Psychologist. 2020;75(2):235251. doi:10.1037/amp0000517

[34] Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S102S138. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee

[35] Eisenberg D, Shikora SA, Aarts E, et al. 2022 American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO): indications for metabolic and bariatric surgery. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2022;18(12):13451356. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2022.08.013

[36] ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 8. Obesity and weight management for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of care in diabetes2023. Diabetes Care. 2022;46(Suppl 1):S128S139. doi:10.2337/dc23-S008

Overweight and Obesity Prevention

You and your child should each see a healthcare provider once a year to monitor changes in body mass index (BMI). Your provider or your childs pediatrician may recommend lifestyle changes if BMI regularly increases. This is to prevent you or your child from developing overweight or obesity.

What factors contribute to a healthy or unhealthy weight?

Many factors can contribute to a persons weight. These include your:

- Behavior or lifestyle habits, such as lack of physical activity, sedentary behaviors, a poor diet, and poor sleep habits

- Environment, such as where you live and the lifestyle habits within your family

- Economic factors that can influence the foods that you can afford and other lifestyle habits

- Family history and genetic

- Metabolism (the way your body converts food into energy)

Additionally, people from communities with fewer resources, who have food insecurity, or who face other similar issues tend to have a higher risk of developing obesity. NHLBI-funded research found that unhealthy lifestyle habits can worsen the risk of obesity in people who have a genetic risk of obesity. You cannot change some of these factors; for example, the genes you inherit from your parents that determine how tall you are. But you can replace unhealthy habits with healthy ones.

Learn more about our research on obesity.

The Prevention and Treatment of Obesity

Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014 Oct; 111(42): 705713.

The Prevention and Treatment of Obesity

, Prof. Dr. med.,1 , Prof. Dr. med.,2 and , Prof. Dr. med.3,*

Alfred Wirth

1Bad Rothenfelde

Martin Wabitsch

2Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Section of Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes, University Medical Center Ulm, Ulm

Hans Hauner

3Else Kroener-Fresenius-Center for Nutritional Medicine, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technische Universitt Mnchen, Munich

1Bad Rothenfelde

2Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Section of Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes, University Medical Center Ulm, Ulm

3Else Kroener-Fresenius-Center for Nutritional Medicine, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technische Universitt Mnchen, Munich

Received 2014 Jul 17; Accepted 2014 Jul 23.

Abstract

Background

The high prevalence of obesity (24% of the adult population) and its adverse effects on health call for effective prevention and treatment.

Method

Pertinent articles were retrieved by a systematic literature search for the period 2005 to 2012. A total of 4495 abstracts were examined. 119 publications were analyzed, and recommendations were issued in a structured consensus procedure by an interdisciplinary committee with the participation of ten medical specialty societies.

Results

Obesity (body-mass index [BMI] 30 kg/m2) is considered to be a chronic disease. Its prevention is especially important. For obese persons, it is recommended that a diet with an energy deficit of 500 kcal/day and a low energy density should be instituted for the purpose of weight loss and stabilization of a lower weight. The relative proportion of macronutrients is of secondary importance for weight loss. If the BMI exceeds 30 kg/m2, formula products can be used for a limited time. More physical exercise in everyday life and during leisure time promotes weight loss and improves risk factors and obesity-associated diseases. Behavior modification and behavioral therapy support changes in nutrition and exercise in everyday life. With respect to changes in lifestyle, there is no scientific evidence to support any particular order of the measures to be taken. Weight-loss programs whose efficacy has been scientifically evaluated are recommended. Surgical intervention is more effective than conservative treatment with respect to reduction of bodily fat, improvement of obesity-associated diseases, and lowering mortality. Controlled studies indicate that, within 1 to 2 years, a weight loss of ca. 4 to 6 kg can be achieved by dietary therapy, 2 to 3 kg by exercise therapy, and 20 to 40 kg by bariatric surgery.

Conclusion

There is good scientific evidence for effective measures for the prevention and treatment of obesity.

Obesity is a significant issue for health policy because it is so widespread in the population as a whole, and because of the high risk of complications it carries (1). According to the findings of the DEGS study (Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland, German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults) carried out between 2008 and 2011 by the Robert Koch Institute in a cohort representative of the whole population, 23.3% of men and 23.9% of women were obese (2). The prevalence of obesity increases four-fold with age in both men and women in an age-dependent manner. In the period from 1999 to 2009, in particular, the prevalence of persons with a body mass index (BMI) of 35 kg/m2 or higher rose markedly (3).

Obesity is implicated in a wide variety of health problems such as impaired sense of wellbeing and impaired quality of life, numerous complications, high frequency of sick leave and early retirement, and increased mortality. The health-related complications are due to the increased proportion of body fat and associated disturbances of endocrine/metabolic function and due to increased mechanical load. Fatty tissue does not only store energy, it is also an active endocrine organ that is closely connected to the intermediary metabolism.

Method

Twelve experts from ten medical professional societies/organizations took part in developing the Guideline (ebox). The literature search and evaluation of the evidence were carried out by the German Agency for Quality in Medicine (ZQ, rztliches Zentrum fr Qualitt in der Medizin) on behalf of the German Obesity Association (DAG, Deutsche Adipositas-Gesellschaft). Five guidelines identified as relevant were evaluated using the German instrument for the methodical evaluation of guidelines (DELBI, Deutsches Leitlinien-Bewertungsinstrument) and the key recommendations extracted. A total of 4495 abstracts were identified as published during the period covered by the literature search (from 2005 to March 2012). The MedLine database was searched via www.pubmed.org. In addition, other relevant publications dated up to April 2014 and located by the experts in a manual search were taken into account, so it may be assumed that no studies were missed that would fundamentally undermine the statements contained in the Guideline (). The selection (defined inclusion and exclusion criteria) and evaluation of the studies (in accordance with SIGN, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, ) were carried out by personnel of the ZQ. The recommendations formulated on the basis of the evidence tables and source guidelines were agreed during structured consensus conferences and during the Delphi process that followed (moderated by the ZQ). The final version of the Guideline was produced after external expert review.

eBox

Participating societies, organizations, and experts

The Guideline members represent the following medical societies and organizations

German Obesity Association (DAG, Deutsche Adipositas-Gesellschaft)

Prof. H. Hauner

Prof. D. Kunze

Dr. M. Teufel

Prof. M. Wabitsch

Prof. A. Wirth

German Diabetes Association (DDG, Deutsche Diabetes-Gesellschaft)

German Society of Nutritional Medicine (DGEM, Deutsche Gesellschaft fr Ernhrungsmedizin)

German Nutrition Society (DGE, Deutsche Gesellschaft fr Ernhrung)

German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM, Deutsche Gesellschaft fr Allgemeinmedizin)

German Society of Sports Medicine and Prevention (DGSP, Deutsche Gesellschaft fr Sportmedizin und Prvention)

German Eating Disorder Society (DGESS, Deutsche Gesellschaft fr Essstrungen)

German College for Psychosomatic Medicine (DKPM, Deutsches Kollegium fr Psychosomatische Medizin)

German Society of Psychosomatic Medicine and Medical Psychotherapy (DGPM, Deutsche Gesellschaft fr Psychosomatische Medizin)

Surgical Working Group for Adiposity Therapy (CAADIP, Chirurgische Arbeitsgemeinschaft fr Adipositastherapie) of the German Society for General and Visceral Surgery (DGAV, Deutsche Gesellschaft fr Allgemein- und Viszeralchirurgie)

Obesity Surgery Patient Support Group (AcSDeV, Adipositaschirurgie-Selbsthilfe Deutschland)

Standing Commission on the Maintenance and Updating of DAG Guidelines (Stndige Kommission zur Pflege und Aktualisierung der DAG-Leitlinien)

eTable

Classification (SIGN 2010) and evaluation of evidence. Evidence levels (EL) were divided into sublevels using + and signs.

| Evidence level | Description | |

| 1 | 1++ | High-quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a very low risk of bias |

| 1+ | Well-conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a low risk of bias | |

| 1 | Meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a high risk of bias | |

| 2 | 2++ | High quality systematic reviews of case control or cohort studies High quality case control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding or bias and a high probability that the relationship is causal |

| 2+ | Well conducted case control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding or bias and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal | |

| 2 | Case control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding or bias and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal | |

| 3 | 3 | Nonanalytic studies, e.g., case reports, case series |

| 4 | 4 | Expert opinion |

| Recommendation grade (RG) | Description | |

| A | Strong recommendation | |

| B | Recommendation | |

| 0 | No recommendation | |

| Consensus strength | Percentage of participants in agreement | |

| Strong consensus | >95% of participants | |

| Consensus | >7595% of participants | |

| Majority agreement | >5075% of participants | |

| No consensus | <50% of participants |

The statements below reproduce the main content of the Guideline. The complete texts are available at www.adipositas-gesellschaft.de.

Obesitya disease

The World Health Organization (WHO), the German Federal Court, the European Parliament, and the German Obesity Association regard obesity as a chronic disease caused by a complex interaction between genetic factors and environmental or lifestyle factors, which carries increased morbidity and mortality and needs lifelong treatment. Because it is a heterogeneous disorder, individualized assessment, risk stratification, and treatment are required.

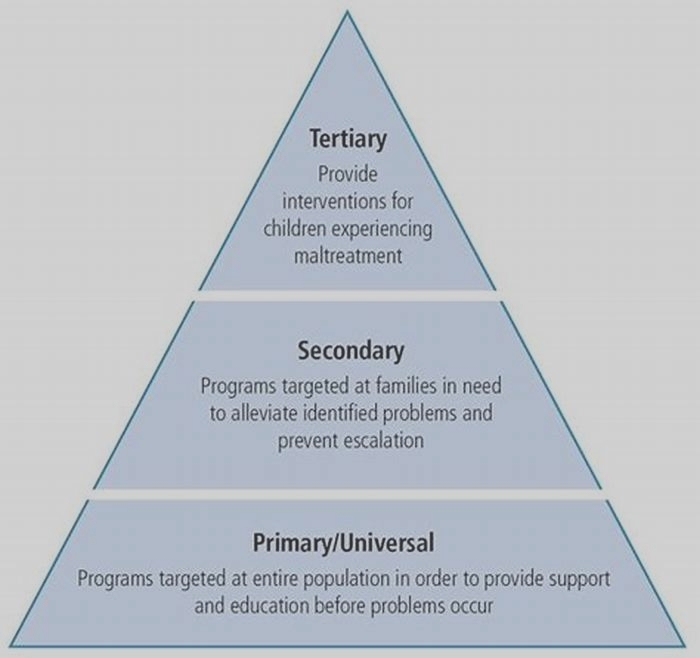

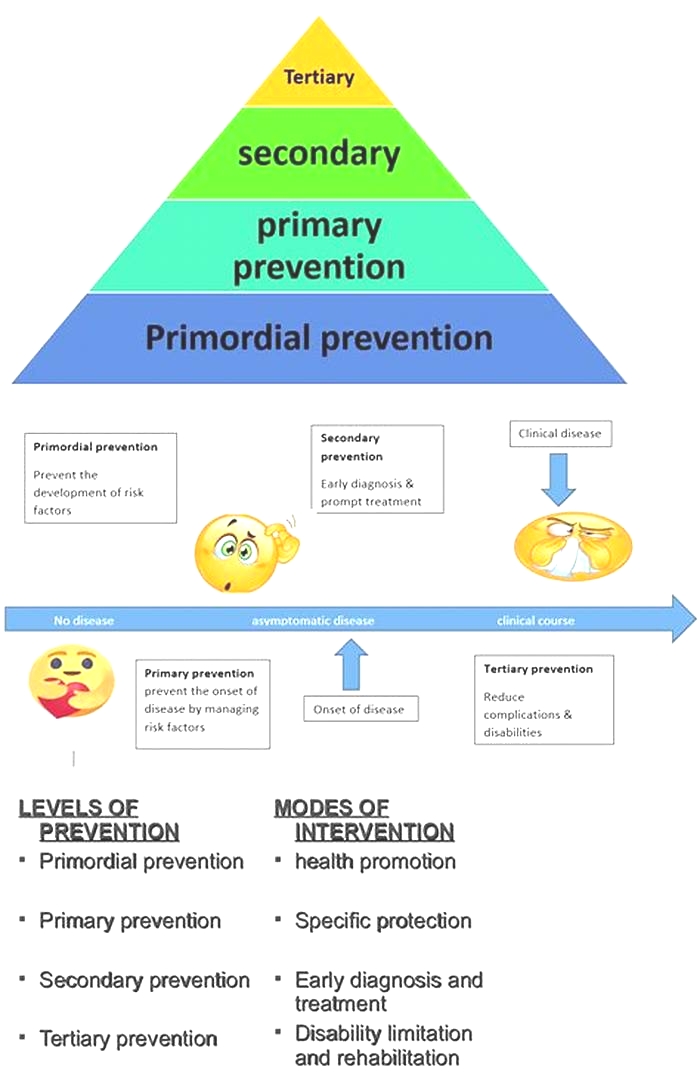

Prevention of obesity

Given that obesity is so prevalent, and given how difficult it is to treat, prevention is particularly important. To prevent overweight and obesity, people should eat and drink according to their nutritional needs, get regular exercise, and check their weight regularly (evidence level [EL] 14, recommendation grade [RG] A, ). So far as nutrition is concerned, they should consume less food with a high energy density and more food with a low energy density (EL 2, RG B). Foods that have a low energy density due to their high water or fiber content, such as wholegrain products, fruit, and vegetables, are comparatively more filling and have a low energy content (4). According to the German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM, Deutsche Gesellschaft fr Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin), there is insufficient evidence to support the proposition that persons with a BMI over 25 kg/m2 should avoid energy-dense foods. The German Society of Nutritional Medicine (DGEM, Deutsche Gesellschaft fr Ernhrungsmedizin) also says that a Mediterranean diet helps prevent overweight and obesity.

The Guideline also states that consumption of alcohol, fast food, and sugary drinks should be reduced (EL 2, RG B) (5). Fast food often contains a high proportion of fat and sugar and is thus very energy-dense (6). Not only drinks sweetened with sugar, but fruit juices and juice-based drinks too, have a high sugar content and are not very filling (7).

An inactive lifestyle with frequent sitting watching television or on the internet and similar activities promotes weight gain (EL 14, RG B). Getting exercise in everyday activities and as a leisure pursuit has a preventive effect. This goal is best achieved by endurance-focused physical exercise (use of large muscle groups) for more than 2 hours per week (8).

Who should lose weight?

Whether treatment is indicated for overweight and obesity depends on patient BMI and body fat distribution, taking into account any co-morbidities, risk factors, and patient preferences (EL 4, RG A). The following are indicators for treatment:

Weight loss is contraindicated for persons with wasting diseases and for pregnant women.

Treatment for obesity

Goals

Treatment goals should be realistic and adapted to the individual patient (e.g., experiences, resources, risks) (EL 4, RG B). Goals are:

Long-term weight reduction:

Improvement in obesity-related risk factors

Reduction in obesity-related diseases

Lowering of risk of early death

Prevention of inability to work and early retirement

Reduction of psychosocial disorders

Improvement of quality of life

Dietary therapy

Obese individuals should received personalized nutritional recommendations adapted to their therapeutic goals and risk profile (EL 4, RG A). This can only be successful over the long term if the patient agrees to a change in lifestyle and recommendations that are practicable in daily life. No valid studies have been published on this recommendation.

To carry out dietary therapy, nutritional counseling (individual or in groups) should be offered within the program of medical management (EL 1, RG A). Group sessions are usually more effective than individual sessions. The DGEM gives a recommendation grade of B rather than A.

For weight reduction, patients should be recommended forms of nutrition that over a long enough time lead to an energy deficit but do not impair health (EL 14, RG A).

To reduce body weight, the aim should be to follow a reduction diet that will produce an energy deficit of about 500 kcal/day, or more in individual cases (EL 14, RG B). To achieve this, various nutrition strategies may be employed (EL 14, RG 0):

The DGEM states that wide-ranging literature exists for this recommendation and a recommendation grade of A is justified.

An energy deficit of 500 to 600 kcal/day will allow weight loss to occur at around 0.5 kg/week over a period of 12 up to a maximum of 24 weeks (9). The consumption of fat, which in Germany is still high, can be reduced by simple steps (10). A low-carb diet will lead to sharper weight loss at the beginning than other diets, but after a year the difference can no longer be seen (11). Several large studies in the past few years have shown convincingly that the macronutrient composition (ratio of fats to carbohydrates to protein) has no relevance for weight loss () (12, 13). Various reduction diets (fat reduction alone, low-carb diet, reduced-energy balanced diet, Mediterranean diet) lead to loss of around 4 kg in 1 to 2 years (). Individual experience, knowledge, and resources are more important than nutrient relationships. The DGEM regards a recommendation grade of B rather than 0 as justified for this procedure.

Weight loss on four different types of diet with different ratios of macronutrients. Study in 811 men and women (BMI 25 to 40 kg/m2) aged 30 to 70 years and with various carbohydrate:protein:fat ratios (%) (13).

Table 1

Effect of various forms of dietary therapy on body weight in overweight/obese persons*

| No. of participants | Study type | Duration | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-fat diet only | ||||

| 1910 | Meta-analysis of 19 RCTs in adults | 212 months | 3.2 kg (1.9 to 4.5 kg),extra weight loss t (2.6 kg) per 10 kg higher weigh | (10) |

| Dietary therapy | ||||

| 6386 intervention 5407 "usual care | Meta-analysis of 46 RCTs | > 4 months | Weight reduced by 1.9 BMI unitsor 6% of initial weight | (14) |

| Low-carbohydrate vs. low-fat weight reduction diet | ||||

| 447 | Meta-analysis of 5 RCTs | 6 months, 12 months | After 6 months:greater weight loss of 3.3 kg(5.3 to 1.4 kg) on low-carbohydrate diet;after 12 months:difference in weight no longer seen(1.0 kg [3.5 to 1.0 kg, n.s.]) | (11) |

| High-protein vs. low-protein diet | ||||

| 1086 | Meta-analysis of 15 RCTs | n.d. | High-protein diet leads to a greater reductionin body weight, by0.39 kg (1.43 to 0.65 kg, n.s.) | (15) |

| Mediterranean diet | ||||

| 3436 | Meta-analysis of 16 RCTs in adults | n.d. | All studies:1.75 kg (2.86 to 0.64 kg),studies with restricted calories:3.88 kg (6.54 to 1.21 kg) | (16) |

| Recent original data | ||||

| 811 | RCT,various combinations of macronutrients:20% F/ 15% P/ 65%CH 20% F/ 25% P/ 55%CH 40% F/ 15% P/ 45%CH 40% F/ 25% P/ 35% CH | 24 months | After 6 months,weight loss of 6 kg in all arms,after 2 years moderate weight loss of 4 kg,no difference between diets | (13) |

| 772 | RCT, commercial group programvs. "standard care under family doctor | 12 months | 5.1 vs. 2.25 kg (LOCF),dropout rate: 42% | (28) |

To attain the therapeutic objective, the use of formula products supplying 800 to 1200 kcal/day may be considered (EL 1, RG 0). This form of nutrition is recommended for persons with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or more for a maximum of 12 weeks; weight loss of 0.5 to 2.0 kg/week may be expected (17). This treatment should be carried out under a physician's supervision because of the increased risk of side effects (EL 1, RG A). In the opinion of the DGEM, formula diets have been well investigated in high-quality cohort studies and for this reason a recommendation grade of A rather than 0 is favored. Formula diets are the most effective diet method for initial weight reduction.

Extremely one-sided diets should not be recommended because of the high medical risks they entail and their lack of long-term success (EL 4, RG A). Diets involving extreme nutrient distributions (e.g., so-called crash diets) are widely followed in Germany. No robust studies on their effectiveness and safety have been published. Since their effectiveness and safety are unknown, they cannot be recommended.

Increased exercise

Effective weight loss requires >150 min/week of exercise with an energy consumption rate of 1200 to 1800 kcal/week (8). Strength training alone is not very effective for weight reduction (EL 24, RG B) (18). The amount of energy used up during exercise is often overestimated. When large muscle groups are used, the intensity is moderate to high, and the exercise work is of long duration, weight loss can be expected. Well-controlled studies and meta-analyses show a weight reduction of about 2 kg and about a 6% loss of abdominal fat in 6 to 12 months ().

Table 2

Effects of physical activity on weight loss in terms of body weight and abdominal fat, depending on type of activity, intensity, and duration*

| No. | Characteristics | Duration | Participation (%) | Physical activity | Body weight (kg) | Abdominal fat (%) | Comments | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Intensity | Duration | ||||||||

| 202 | Men and women, 4075 years | 12 months | 93 | Endurance training | 6085 % max. heart rate | 6 x 60 min/week | Women 1.4 (1.8) men 1.8 (1.8) | Women 4.8 men 7.5 | Association found between duration of activity and weight changes and proportion of body fat ("doseeffect relationship) | (19) |

| Controls | Women +0.7 (+0.9) men 0.1 (+0.9) | No significant changes | ||||||||

| 249 | Men and women, 1870 years | 3 months | Strength training | 812 repeats | 3 x 30 min/week | +0.7 (2.4) | 0,5 | Well-controlled study with supervision and food logs. Strength training had no measurable effect, not even in combination with endurance training. | (20) | |

| 90 | Endurance training | Approx. 75% max. O2 uptake | 3 x 30 min/week | 2.0 (3.8) | 8.4 | |||||

| 82 | Strength and endurance training | See above | 6 x 30 min/week | 2.1 (3.2) | 7.1 | |||||

| 1847 | 14 studies, meta-analysis | 12 weeks to 12 months | Endurance training | Varied widely | Varied widely | 1.7 (2.29 to 1.11) | Only two studies had a training duration greater than 225 min/week. There was a positive doseeffect relationship. | (21) | ||

| 3476 | 43 studies, Cochrane | 12 months | Endurance training | Varied widely | Varied widely | 2.0 (2.1 to 0.7) | (22) |

It should be ascertained that overweight and obese persons do not have any contraindications to additional physical activity. This is particularly the case for patients with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or higher (EL 4, RG B).

Overweight and obese persons should have the health advantages (metabolic, cardiovascular, and psychosocial) of physical activity explained to them, which accrue irrespective of loss of weight (EL 4, RG A). Even in obese individuals, the health value of increased exercise is seen in more than just a loss of weight (23).

Interventions for behavior modification

Interventions based on a behavioral approach, in a group or individual setting, should form part of a program of weight reduction (EL 1, RG A). The intervention should be aimed primarily at altering lifestyle in terms of nutrition and exercise and may be carried out by qualified non-psychotherapists. If the symptoms accompanying overweight or obesity are more serious (e.g., co-morbid depression, eating disorders, motivation problems), psychiatrists or psychotherapists should be involved in the patient management, and patients should be supported in their dietary therapy and exercise (24).

Various strategies are available for intervention. They should be adapted to the individual situation and the wishes of the patient involved (25) (box).

Box

Strategies for weight reduction may have the following psychotherapeutic elements (EL 12. RG 0)

Self-observation of behavior and progress (body weight, amount eaten, exercise)

Practicing flexible, controlled eating and exercise behavior (as opposed to rigid behavioral control)

Stimulus control (stimulus = external trigger for eating)

Strategies for handling returning weight gain

Social support

Cognitive restructuring (modification of dysfunctional thought patterns)

Agreeing goals

Problem-solving training/conflict resolution training

Social competence training/assertiveness training

Reinforcement strategies (e.g., rewarding changes)

Preventing relapse

Weight reduction program

Obese patients should be offered weight reduction programs that are adapted to their individual situation and targeted at the therapeutic goals (EL 4, RG B). The weight reduction programs should include the elements of the basic program (exercise, diet, and behavioral therapy) (EL 12, RG A). , which gives an overview, includes only programs for which published data are available.

Table 3

Commercial programs for weight reduction in Germany for which at least one study has been published in a peer-reviewed journal*

| "Ich nehme ab*1 (DGE) | "Abnehmen mit Genuss*2 (AOK) | Weight Watchers | Bodymed | M.O.B.I.L.I.S | Optifast-52 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | Around 30 | 31 | 31,4 | 33,4 | 35,7 | 40,8 |

| Number of participants | Various studies | 45 869 | 772 (377 Weight Watchers) | 665 | 5025 | 8296 |

| Formula diet | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Probands weighed | Yes | Self-reported | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| kg (1 year) | Not stated | Not stated | 5.1 (LOCF, Weight Watchers) 2.3 (LOCF, controls) | 9.8 (LOCF) | 5.1 (BOCF) | 16.4 (LOCF) |

| kg (1 year) women | 2.3/2.0/ 1.3 | 2.2 (BOCF) | Not stated | Not stated | 5.0 (BOCF) | 15.2 (LOCF) |

| kg (1 year) men | 4.1 | 2.9 (BOCF) | Not stated | Not stated | 5.9 (BOCF) | 19.4 (LOCF) |

| Dropouts | 16%35% | 51% | 39% (Weight Watchers) | 23% | 14% | 42% |

| Type | RCT | Observation | RCT | Observation | Observation | Observation |

| Study quality | RCT studies with and without personal counseling | All participants in Germany from 2006 to 2010 | RCT outcome in comparison to standard advice from doctor | Selected sample (from approx. 500 Bodymed centers in Germany) | 316 groups from 2004 to 2011 | All participants, all centers in Germany from 1999 to 2007 |

| Reference | (26) | (27) | (28) | (29) | (30) | (31) |

The DGEM mentions that obese persons should only be offered programs that have received a positive assessment, which are geared to the individual situation and the therapeutic goals. Programs whose effectiveness is not clear, because (for example) there are no measured data to show the course of body weight over time, should be excluded.

Weight-reducing drugs

Drug therapy should only be carried out in combination with a basic program (diet, exercise, behavioral therapy). The only drug that may be considered is orlistat (EL 1, RG A). Orlistat treatment is indicated in patients with a BMI above 28 kg/m2 who also have other risk factors or co-morbidities, or with a BMI 30 kg/m2 who have less than 5% weight loss after 6 months on the basic program (32).

Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and a BMI 30 kg/m2 may, if their glycemic control is inadequate on metformin, also use GLP-1 mimetics and SGLT2 inhibitors (EL 1, RG 0). These drugs should be considered as an alternative to antidiabetic drugs that promote weight increase, such as sulfonylureas, glinides, glitazones, and insulin (33).

The DEGAM states that insufficient study data exist for GLP-1 analogs in relation to clinical end points. It points out that they may be associated with an increased risk of pancreatic disease.

Drugs such as amphetamines, diuretics, human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG), testosterone, thyroxine, and growth hormones, and medical products / dietary supplements should not be recommended as a way to lose weight (EL 4, RG A). The drugs have an unacceptable riskbenefit ratio, and in regard to the medical products and dietary supplements, evidence of their effectiveness is lacking.

Long-term weight stabilization

Measures to stabilize body weight long term should take into account aspects of diet, exercise, and behavioral therapy together with the motivation of the patient involved (EL 4, RG B).

To support weight stabilization, treatments and consultations should be made available over the long term after successful weight loss, and should include cognitive behavioral therapy (EK 1, RG A) (34).

Patients should be advised, after a period of weight reduction, to maintain an increased level of physical exercise (EL 12, RG A). Experience has shown that almost all patients who maintain their weight after a period of weight loss have remained or become physically active (35). After losing 7 to 14 kg, physically active persons regain half their lost weight within 1 to 2 years ().

Table 4

Weight stabilization: change in body weight and abdominal fat due to increased physical activity (phase 2) following weight reduction (phase 1)*

| Number | Characteristics | Overall duration | Phase 1: Weight reduction (kg) by reduction diet and exercise | Phase 2: Physical activity | Comments | Reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Participation (%) | Intensity | Energy use/duration | Body weight (kg) | Abdominal fat (%) | ||||||

| 202 | Men and women 2550 years | 30 months | 7.7 kg in 6 months | Walking | 79 | Approx. 1200 kcal/week | +6.7 kg in 24 months | Even high activity cannot entirely prevent some weight gain | (36) | ||

| 15.1 kg in 6 months | Walking | 77 | > 2500 kcal/week | +3.0 kg in 24 months | |||||||

| 97 | Men and women 2146 years | 18 months | 12.3 kg in 6 months by reduction diet | Treadmill | 82 | 80% max. heart rate | 2 x 40 min/week | +3.1 kg in 12 months | +1.6 | Endurance and strength training reduce gain in weight and abdominal fat | (37) |

| Strength apparatus | 79 | 80% 1RM | 2 x 40 min/week | +3.9 kg in 12 months | +0 | ||||||

| Control group | +6.1 kg in 12 months | +25 | |||||||||

| 2796 | Men and women over 18 years on the registry | >1 year | Weight reduction of > 13.6 kg | Walking 81% Weight training 29% Cardio machines 15% | Varied widely | > 1000 kcal/week 25% | Weight was maintained for >1 year if energy use of 2621 kcal/week, corresponding to activity of 6075 min/day with moderate intensity or 3445 min/day with high intensity, was achieved | (38) | |||

| > 3000 kcal/week 35% |

Patients should be told that a low-fat diet will help prevent weight regain (EL 12, RG B) (39). In persons who lost 12 to 24 kg on a very low calorie diet, weight regain of >5 kg was seen after 1 to 2 years on a reduced-energy balanced diet ().

Table 5

Weight maintenance after weight reduction by change of eating habits*

| Studies/meta-analysis | Phase 1: Weight loss | Phase 2: Weight maintenance | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of follow-up | Weight change | |||

| Meta-analysisof 29 US studies | Average VLCD: 24.1 kgREMD: 8.8 kg | 4.5 years (VLCD: 55% ofinitial participants,LCD: 80% of participants) | VLCD: 6.6% (5.6 to 7.5%)of initial weightREBD: 2.1% (1.6 to 2.7%);no difference between sexes;with more activity: 12.5%(11.2 to 13.7%) | (40) |

| Meta-analysisof 46 RCTs(Dietary counseling vs."usual care) | Mean weight loss of1.9 BMI units after12 months (corresponds to 6%) | 6 to 48 months | Regain ofbody weight by 0.02 to0.03 BMI units per month(corresponds to approx 1 kg/year) | (14) |

| Meta-analysisof 20 RCTs | Weight loss of12.3 kg on VLCD or LCD(< 1000 kcal/day) | 18 to 36 months | Drugs:Effect of +3.5 kg, 3 RCTs,658 participants | (e1) |

| 10 to 26 months | Meal replacements:+3.9 kg, 4 studies,372 participants | |||

| 3 to 12 months | High-protein diet:+1.5 kg, 6 studies,865 participants | |||

| 6 months | Other types of diet:+1.2 kg, 3 studies564 participants | |||

| 3 to 14 months | Dietary supplements:+/0 kg, 6 studies,261 participants | |||

| 6 to 12 months | Exercise program:+0.8 kg, 5 studies,347 participants |

Regular weighing contributes to better weight stabilization after successful weight loss (EL 4, RG B) (e2).

Surgical intervention in extremely obese patients

For extremely obese patients, surgical intervention should be considered (EL 13, RG A). Compared to conservative treatment, surgical treatment is more effective in terms of body fat reduction, improvement of obesity-related diseases, and reduction of mortality risk (e3 e5) ().

Commonly used surgical methods to treat extreme obesity

Sleeve gastrectomy

Gastric banding

Gastric bypass

(From: Runkel N, et al.: Clinical practice guideline: Bariatric surgery. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2011; 108(20): 3416).

Obesity surgery is indicated according to BMI as follows, if all conservative treatment methods have been unsuccessful (EL 4, RG A):

Grade III obesity (BMI 40 kg/m2) or

Grade II obesity (BMI 35 kg and <40 kg/m2) with significant co-morbidities (e.g., type 2 diabetes) or

Grade I obesity (BMI 30 and <35 kg/m2) in patients with type 2 diabetes (special cases)

If multimodal conservative therapy for 6 months leads to 10% weight loss in patients with a BMI of 35 to 39.9 kg/m2 and 20% in those with a BMI of 40 kg/m2, surgery should be considered (1). The DGEM states: surgery is indicated in patients with a BMI 40 kg/m2 if 10% of the initial weight has been lost. For patients with type 2 diabetes, the recommendation grade is B, as the data are insufficient.

Surgical treatment can also be given as a primary therapy, without any preceding conservative treatment, if conservative treatment is judged to have no chance of success or the patient's health does not allow surgery to be delayed in order to attempt improvement by weight reduction (EL 4, RG 0). Patients with severe concomitant disease, a BMI 50 kg/m2, and difficult psychosocial circumstances are eligible. The DGEM regards surgery as indicated in patients who are immobile, in whom diet-based treatment has failed, and in those with a high insulin requirement.

Before surgery, patients should undergo an assessment that includes metabolic, cardiovascular, psychosocial, and dietary details (EL 4, RG A). After bariatric surgery, lifelong interdisciplinary follow-up is required (EL 4, RG A) (e6). For quality assurance, patients who undergo weight loss surgery should be entered in a central national register (EL 4, RG B).

Key Messages

Obesity (BMI 30 kg/m2) is a chronic disease.

The high prevalence of obesity in adults (24%) means that effective prevention and treatment are required.

For weight loss in obesity, and stabilization at the reduced weight, a diet resulting in an energy deficit of 500 kcal/day is effective. A low-energy diet is recommended; the ratios between macronutrients (fat, carbohydrates, protein) is of secondary importance.

Behavior modification supports changes in diet and exercise in everyday living.

In extremely obese patients, surgical treatment should be considered.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Kersti Wagstaff, MA.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Professor Hauer has received consultancy fees from Weight Watchers International and Apothecom (advisory boards). He has received third-party funding from Weight Watchers International and from Riemser GmbH and Certmedica.

Professor Wirth has received consultancy fees from Riemser GmbH.

Professor Wabitsch has received consultancy fees from Johnson and Johnson Medical GmbH.

References

1.

World Health Organization Obesity - preventing and managing the global epidemic. Technical Report Series 894. Geneva: 2000. Report of a WHO Consultation on obesity. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]2.

Kurth BM. Erste Ergebnisse aus der "Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS) Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2012;55:980990. [Google Scholar]3.

Statistisches Bundesamt Mikrozensus - Fragen zur Gesundheit - Krpermae der Bevlkerung. 2011 [cited: 2013] [Google Scholar]4.

Bes-Rastrollo M, van Dam RM, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Li TY, Sampson LL, Hu FB. Prospective study of dietary energy density and weight gain in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:769777. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]5.

Sayon-Orea C, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Bes-Rastrollo M. Alcohol consumption and body weight: a systematic review. Nutr Rev. 2011;69:419431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]6.

Rosenheck R. Fast food consumption and increased caloric intake: a systematic review of a trajectory towards weight gain and obesity risk. Obes Rev. 2008;9:535547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]7.

Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:667675. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]8.

Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, Manore MM, Rankin JW, Smith BK. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand: Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:459471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]9.

Witham MD, Avenell A. Interventions to achieve long-term weight loss in obese older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2010;39:176184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]10.

Astrup A, Grunwald GK, Melanson EL, Saris WH, Hill JO. The role of low-fat diets in body weight control: a meta-analysis of ad libitum dietary intervention studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:15451552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]11.

Nordmann AJ, Nordmann A, Briel M, et al. Effects of low-carbohydrate vs low-fat diets on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:285293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]12.

Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:229224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]13.

Sacks FM, Bray GA, Carey VJ, et al. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:859873. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]14.

Dansinger ML, Tatsioni A, Wong JB, Chung M, Balk EM. Meta-analysis: the effect of dietary counseling for weight loss. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:4150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]15.

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Long-term effects of low-fat diets either low or high in protein on cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr J. 2013;12 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]16.

Esposito K, Kastorini CM, Panagiotakos DB, Guigliano D. Mediterranean diet and weight loss: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2011;9:112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]17.

Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults - The Evidence Report National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6:51209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]18.

Ismail I, Keating SE, Baker MK, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of aerobic vs:resistance exercise training on visceral fat. Obes reviews. 2012;13:6891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]19.

McTiernan A, Sorensen B, Irwin ML, et al. Exercise effect on weight and body fat in men and women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:14961512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]20.

Slentz CA, Bateman LA, Willis LH, et al. Effects of aerobic vs: resistance training on visceral and liver fat stores, liver enzymes, and insulin resistance by HOMA in overweight adults from STRRIDE AT/RT. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E1033E1039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]21.

Thorogood A, Mottillo S, Shimony A, et al. Isolated aerobic exercise and weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Medicine. 2011;124:747755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]23.

Ghner W, Schlatterer M, Seelig H, Frey I, Berg A, Fuchs R. Two-year follow-up of an interdisciplinary cognitive-behavioral intervention program for obese adults. J Psychol. 2012;146:371391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]24.

Anderson JW, Reynolds LR, Bush HM, Rinsky JL, Washnock C. Effect of a behavioral/nutritional intervention program on weight loss in obese adults: a randomized controlled trial. Postgrad Med. 2011;123:205213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]25.

Shaw K, O'Rourke P, Del MC, Kenardy J. Psychological interventions for overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 CD003818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]26.

Scholz GH, Flehming G, Scholz M, et al. Evaluation des Selbsthilfeprogramms "Ich nehme ab": Gewichtsverlust, Ernhrungsmuster und Akzeptanz nach einjhriger beratergesttzter Intervention bei bergerwichtigen Personen. Ernhrungs-Umschau. 2005;52:226231. [Google Scholar]27.

Austel A, Podzuweit F, Tempelmann A, Stotz-Jonas B, Ellrott T. Evaluation eines tailorisierten computergesttzten Gewichtsmanagementsprogramms mit 46000 Teilnehmern. Obes Facts. 2012;5:2829. [Google Scholar]28.

Jebb SA, Ahern AL, Olson AD, et al. Primary care referral to a commercial provider for weight loss treatment versus standard care: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:14851492. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]29.

Walle H, Becker C. LEAN-Studie II: 1-Jahresergebnisse eines ambulanten, rztlich betreuten Ernhrungskonzepts. Adipositas. 2011;1:1524. [Google Scholar]30.

Lagerstrom D, Berg A, Haas U, et al. Das MO.B.I.L.I.S.-Schulungsprogramm: Bewegungstherapie und Lebensstilintervention bei Adipositas und diabetes. Diabet Aktuel. 2013;11:511. [Google Scholar]31.

Bischoff SC, Damms-Machado A, et al. Multicenter evaluation of an interdisciplinary 52-week weight loss program for obesity with regard to body weight, comorbidities and quality of lifea prospective study. Int J Obes. 2012;36:614624. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]32.

Sjstrom L, Rissanen A, Andersen T, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of orlistat for weight loss and prevention of weight regain in obese patients European Multicentre Orlistat Study Group. Lancet. 1998;352:167172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]33.

Monami M, Dicembrini I, Marchionni N, Rotella CM, Mannucci E. Effects of glucagon-like Peptide-1 receptor agonists on body weight: a meta-analysis. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012 672658. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]34.

Ohsiek S, Williams M. Psychological factors influencing weight loss maintenance: an integrative literature review. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2011;23:592601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]35.

Klem ML, Wing RR, McGuire MT, Seagle HM, Hill JO. A descriptive study of individuals successful at long-term maintenance of substantial weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:239246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]36.

Tate DF, Jeffery RW, Sherwood NE, Wing RR. Long-term weight losses associated with prescription of higher physical activitry goals: Are higher levels of physical activity protective against weight regain? Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:954959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]37.

Hunter GR, Brock DW, Byrne NM, et al. Exercise training prevents regain of visceral fat for 1-year following weight loss. Obesity. 2010;18:690695. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]38.

Catenacci VA, Ogden LG, Stuht J, et al. Physical activity patterns in the National Weight Control Registry. Obesity. 2008;16:153161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]39.

Toubro S, Astrup A. Randomised comparison of diets for maintaining obese subjects' weight after major weight loss: ad lib, low fat, high carbohydrate diet v fixed energy intake. BMJ. 1997;314:2934. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]40.

Anderson JW, Konz EC, Frederich RC, Wood CL. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:579584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]E1.

Johansson K, Neovius M, Hemmingsson E. Effects of anti-obesity drugs, diet, and exercise on weight-loss maintenance after a very-low-calorie diet or low-calorie diet: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:1423. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]E2.

Butryn ML, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Consistent self-monitoring of weight: a key component of successful weight loss maintenance. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:30913096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]E3.

Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]E4.

Dixon JB, Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Rubino F. Bariatric surgery: an IDF statement for obese Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2011;28:628642. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]E5.

Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:15671576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]E6.

Slater GH, Ren CJ, Siegel N, et al. Serum fat-soluble vitamin deficiency and abnormal calcium metabolism after malabsorptive bariatric surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:4855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]