What is the primary and secondary prevention of obesity

Prevention Strategies & Guidelines

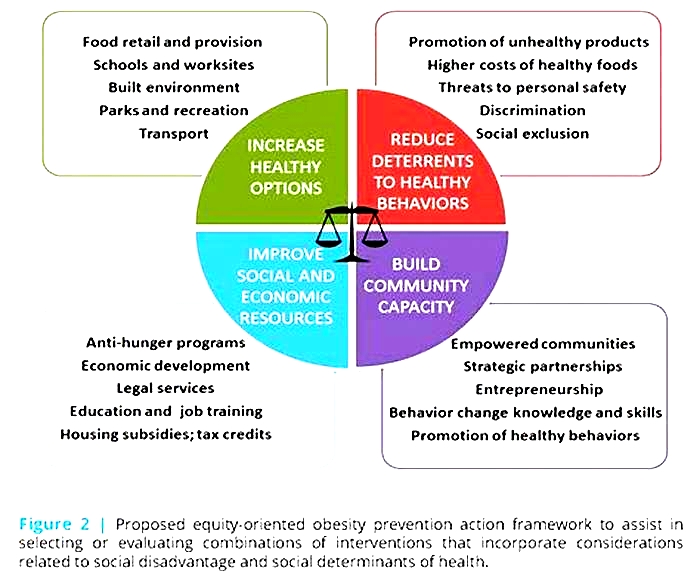

To reverse the obesity epidemic, places and practices need to support healthy eating and active living in many settings. Below are recommended strategies to prevent obesity.

Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity Prevention Strategies

The CDC Guide to Strategies to Increase Physical Activity in the Community [PDF-1.2MB] provides guidance for program managers, policy makers, and others on how to select strategies to increase physical activity.

Physical Activity: Built Environment Approaches Combining Transportation System Interventions with Land Use and Environmental DesignThe Community Preventive Services Task Force recommends built environment strategies that combine one or more interventions to improve pedestrian or bicycle transportation systems with one or more land use and environmental design interventions to increase physical activity.

The CDC Guide to Strategies to Increase the Consumption of Fruits and Vegetables [PDF-2.1MB] provides guidance for program managers, policy makers, and others on how to select strategies to increase the consumption of fruits and vegetables.

The CDC Guide to Breastfeeding Interventions provides state and local community members information to choose the breastfeeding intervention strategy that best meets their needs.

Recommended Community Strategies and Measurements to Prevent Obesity in the United States [PDF-376KB] contains 24 recommended obesity prevention strategies focusing on environmental and policy level change initiatives that can be implemented by local governments and school districts to promote healthy eating and active living.

Early Care and Education Strategies

CDCs framework for obesity prevention, in the ECE setting is known as the Spectrum of Opportunities [PDF-666KB]. The Spectrum identifies ways that states, and to some extent communities, can support child care and early education facilities to achieve recommended standards and best practices for obesity prevention. The Spectrum aligns with comprehensive national ECE standards for obesity prevention address nutrition, infant feeding, physical activity and screen time, Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards (CFOC), 3rd ed.

School Health Guidelines

School Health Guidelines to Promote Healthy Eating and Physical Activity provides nine guidelines that serve as the foundation for developing, implementing, and evaluating school-based healthy eating and physical activity policies and practices for students in grades K-12.

The following resources are designed to assist schools and program coordinators to inform stakeholders and school health services staff on obesity facts, engaging students and managing chronic health conditions.

Community Guide

The Community Guide Obesity Prevention and Control is a free resource to help you choose programs and policies to prevent and control obesity in your community.

Clinical Guidelines

Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents [PDF-3.26MB] This resource summarizes the integrated guidelines develop by the Federal Government to address cardiovascular disease in children and adolescents.

Screening for Obesity in Pediatric Primary Care: Recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Guidance for primary care providers in screening for obesity and offering or referring to comprehensive, intensive behavioral weight management interventions.

The American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity aims to inform pediatricians and other pediatric health care providers about the standard of care for evaluating and treating children with overweight and obesity and related comorbidities. The CPG promotes an approach that considers the childs health status, family system, community context, and resources for treatment to create the best evidence-based treatment plan.

2013 Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular RiskThis is a Report of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines for reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Bookshelf

Multiple consensus committees have established guidelines for the prevention and management of obesity. These include the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the Institute of Medicine (IOM), and others. Common themes in these guidelines include healthy eating and controlling calories, physical activity, behavior modifications, and consideration of medications and surgery when initial efforts are unsuccessful in motivated patients. This guideline summarizes the most recent evidence on obesity management.

Treatment

Management of overweight patients focuses primarily on lifestyle changes such as diet, physical activity, sleep and stress reduction. A combination of physical activity and dietary changes has been found to be most effective for weight loss. If these measures are unsuccessful after 6 months, then medications, surgery, and other referrals may be required.

Small concrete changes that focus on lifestyle change, behavior modification, healthy eating and physical activity are most likely to be successful in the long run. Progress should be measured on lifestyle change as much as weight parameters, as it is known that modifying diet and activity can have positive health consequences even in the absence of weight loss.

Lifestyle counseling. Even within a limited time visit, providers can promote a healthy lifestyle and influence patient behavior.

Lifestyle counseling includes self-management education and support, identifying lifestyle changes, and collaborative goal setting between the provider and patient. The provider works with the patient to identify the patients biggest concern regarding change. Examples of modifiable behaviors to target include physical activity and television viewing. Using open ended questions and listening skills, the provider helps the patient explore any issues and works collaboratively with the patient to establish a self-management goal.

Additional for children and adolescents. Management of obesity involves the entire family. Engagement of family members is important for adults, and parental involvement is critical for children. Lifestyle changes are greatly facilitated by supporting changes in the environment. Individual counseling and web-based weight-loss programs are much less successful in promoting lifestyle changes for children than group-based or family-based treatments. Recent studies have shown that many parents perceive that their overweight child is of normal weight. If the family does not perceive that the child is obese, or if they will not cooperate with lifestyle changes, then office-based interventions for pediatric obesity will not be successful.

Additional for adults. Lifestyle counseling is intended to help patients make informed decisions, identify and overcome barriers, provide health education and appropriate care recommendations, and provide self-management support. Important steps include:

Initiating a discussion about nutrition and physical activity.

Helping the patient set goals.

Encouraging open communication between the patient and health care provider.

Following up on the patients progress.

The healthcare team can be utilized to provide extended support.

Treatment goals. The adverse health outcomes associated with obesity depend on several factors, including the presence of other risks and comorbid conditions, such as cigarette smoking, family history, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, etc. Thus, clinicians should determine treatment goals keeping these in mind, rather than on the basis of weight alone.

General goals of weight management in obese persons are:

Weight loss goals should be individualized and aimed at the long term. Starting points for developing individual goals are summarized in .

Additional for children and adolescents. In growing children, slowing the rate of weight gain while they continue to get taller will result in a decreased BMI over time. For adolescents with BMI at the 99th percentile or higher, 0.5 to 1 pound per week weight loss goals may be reasonable. A simple approach for children and families is the 5-2-1-0 plan promoted by the Lets Move initiative (see ).

Additional for adults. A reduction in body weight by approximately 10 percent over a span of 6 months is a reasonable initial goal for weight loss therapy. This level of modest loss can be maintained over time. Depending on the BMI, this corresponds to an average energy deficit of approximately 500 1000 kcal per day, resulting in a weight loss rate of 1 to 2 pounds per week. The corresponding amounts of food intake in kcal per day for individuals of average height, weight, and activity level are 18002000 for men and 13001500 for women. Individualized targets for reduced calorie intake can be calculated by dietitians or estimated using free online weight loss calorie calculators. An individuals subsequent weight loss strategy will depend upon the initial amount of weight loss.

A greater weight loss (eg, 20% or more over 6 months) may be considered for persons with BMI 35 kg/m2 or those with a significant burden of obesity-related comorbid conditions.

Physical activity. Recommended basic activity goals are presented in along with categories of activity levels, their definitions, and examples.

Additional for children. Children should participate in physical activities that are age-appropriate, enjoyable, and that offer variety. Intensive family-based programs have been found to lead to sustained weight loss in children.

The average child spends 7.5 hours per day in front of a screen, including watching television, using the computer, or playing video games. The more time children spend in front of a screen, the higher their risk of obesity. Children and adolescents should limit their screen time to no more than one to two hours of quality programming daily.

Additional for adults. CDC recommends a gradual increase in physical activity toward a daily goal of 60 to 90 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity to sustain weight loss. To help maintain weight and prevent weight gain, adults should engage in approximately 60 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity activity on most days of the week.

Older adults and those with chronic medical conditions limiting physical activity should be as physically active as their abilities allow. Those at risk of falling should also do exercises to improve balance.

Dietary intervention. General dietary recommendations to promote weight loss are summarized in . These recommendations apply to children and adults.

Additional for children. While the basic interventions are the same as for adults, the focus should be on changing the familys diet, not just the diet of the overweight child.

Additional for adults. Decrease total energy intake by 500 to 1,000 kcal per day to achieve a weight loss of 1 to 2 pounds per week.

Sleep. Short sleep duration is associated with an increased risk for excessive weight gain and obesity. Clinicians should counsel patients and families on appropriate sleep requirements. Recommendations for age-appropriate sleep durations and strategies for good sleep for children and adults are presented in .

Medications. Weight loss medications are not recommended for children or adolescents. For adult patients, medications typically result in only modest to moderate weight loss, but may help prevent further weight gain. Medications may be considered for adults with BMI 30 kg/m2 or with BMI 27 kg/m2 and significant medical complications, if diet and activity modifications do not result in weight loss of 5% at 3 months and 10% after 6 months.

Phentermine (short term only) and orlistat are FDA-approved for weight loss in conjunction with lifestyle intervention when lifestyle intervention alone is unsuccessful. The use of these two approved drugs is described in . Three additional weight loss medications were approved by the FDA in 2012: a combination of phentermine and topiramate (available as Qsymia), liraglutide (Saxenda), and naltrexone/bupropion ER (Contrave). All six drugs are contraindicated in pregnancy use with caution in women of childbearing age.

Metformin led to a 1.5-cm greater decrease in waist circumference; however, its use for obesity is not approved by the FDA and is thus considered an off-label use.

Medications that have been approved for other indications that are employed in off-label use for obesity and can promote short-term modest weight loss include: buproprion, zonisamide, and topiramate. However, the USPSTF found no evidence of benefit regarding maintenance of improvement in weight after discontinuation of these medications.

In general, over-the-counter (OTC) medications are not recommended for weight loss. The exception is the OTC version of orlistat, which is marked as Alli.

Multidisciplinary weight management programs. The most effective strategies for weight management employ a multidisciplinary team working in concert to achieve individualized weight loss goals. At Michigan Medicine information is available at: https://www.uofmhealth.org/conditions-treatments/adult-weight-management

Multidisciplinary teams typically include:

Physician: evaluates, assesses risk, counsels the patient, coordinates care of the team, and can refer to specialists as needed.

Dietitian: delivers tailored nutritional information appropriate to the patients preferences and lifestyle.

Exercise physiologist: assesses a patients capacity for exercise, and prescribes a regimen that can be done at home, at a gym, or in one-on-one sessions.

Behavioral therapist: offers standard behavioral or cognitive behavioral therapy.

Endocrinologist: evaluates for secondary causes of obesity, evaluates and treats complications of obesity such as diabetes, and prescribes pharmacotherapy when lifestyle interventions alone result in little success.

Bariatric surgery. When other approaches have not resulted in adequate weight control, bariatric surgery may be considered. While bariatric surgery results in significantly greater weight loss than conventional treatment for obese adults, surgery is associated with a greater risk of complications and requires lifelong intake of certain micronutrients and vitamins. Bariatric surgery has been found to reduce or resolve obesity-related medical comorbidities including diabetes (depending on duration of the disease) and hypertension.

Bariatric surgery may be considered for patients with a BMI 40 kg/m2, or BMI 35 kg/m2 with weight-related health complications (eg, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, polyarthritis, pulmonary hypertension, sleep apnea, or hyperlipidemia). Before bariatric surgery will be performed, most surgeons and insurers require documented compliance with a medically supervised weight loss program for a minimum of six months (including monthly documentation of weight, dietary, exercise, and lifestyle modifications at each visit) without achieving significant weight loss. The supervised weight loss program usually should have occurred within the past 2 years, although some insurance companies will include the past 4 years. Absolute contraindications to bariatric surgery include pregnancy, lactation, active substance abuse, end-stage cardiovascular disease, severe or uncontrolled psychiatric disorders, and anorexia nervosa. Relative contraindications include unstable medical conditions, end-stage renal disease, active binge eating disorder, or bulimia nervosa.

Managing comorbid conditions. Obese patients frequently have or develop comorbid conditions. The specifics of managing comorbid conditions are beyond the scope of this guideline. See the list of UMHS clinical guidelines for recommendations concerning some common comorbid conditions, including coronary artery disease, depression, diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, and lipid management.

Obesity can affect the diagnosis and treatment of the patients other conditions. The effects are noteworthy for:

Pharmacologic dosing. Based on their pharmacokinetic profile, drugs differ in their volume of distribution depending on the amount of body fat.

Radiologic studies and procedures. The amount of subcutaneous adipose tissue influences the quality of the results of various radiologic modalities. The results of ultrasonography and x-ray examinations are particularly vulnerable to the effects of subcutaneous fat.